Desert Locusts, a strong marker of the consequences of human activity and global warming

The Desert Locust, or Schistocera gregaria by its scientific name, they are species whose physiology (physical appearance, behavior and biochemical components) changes in response to environmental conditions. There are two distinct behaviors when they are alone or in a gregarious state (in a group). Lonely adults are passive and fly in the early evening for food. Whereas individuals belonging to a swarm adopt an extremely voracious group behavior. They circulate from sunrise when the atmosphere is warm, until sunset. They can travel 100 to 150 km per day at heights of up to 2000 meters and fly continuously for more than 20 hours.

How those species reproduce?

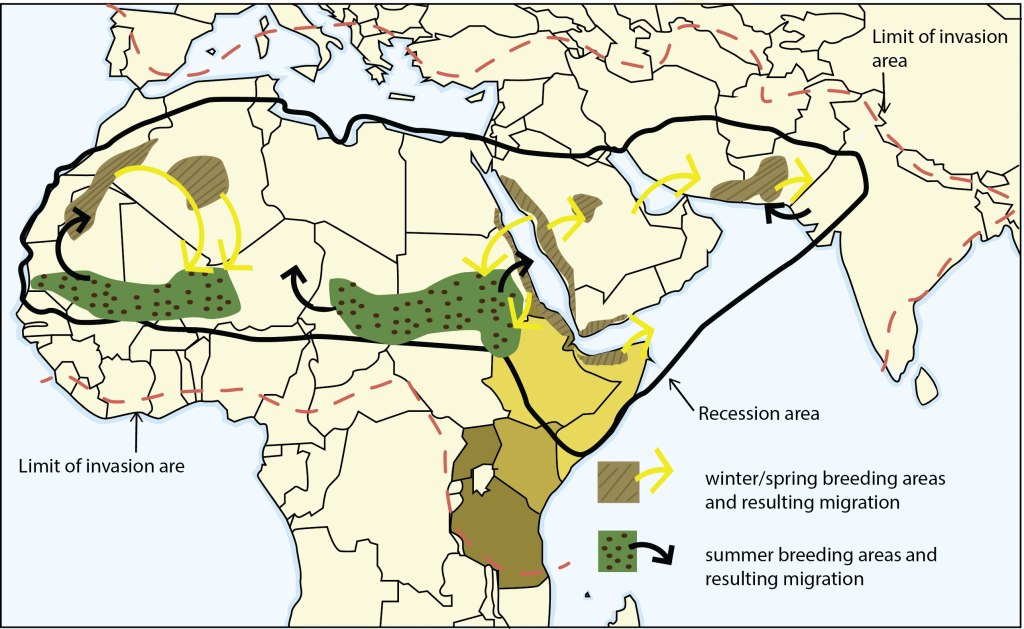

Under normal conditions, the locust is found in low numbers in the deserts of North Africa, the Middle East and Southwest Asia, where less than 20 cm of rainwater falls per year. It lives isolated and seeks shelter in scattered vegetation and lays its eggs in the sandy and moist soil. This arid habitat area covers 16 million square kilometers and includes 30 countries. This is called a recession zone.

When heavy rains fall in this recession zone, locusts will take advantage of them to multiply rapidly. Under optimal conditions, this will give rise to a population increase of 16 to 20 times that of the starting point. And this happening every 3 months.

Once the recession area dries up again, locusts are forced to move towards the remaining patches of vegetation and concentrate by coming into physical contact with each other. Individuals become gregarious: we thus find mass behavior. Gregarization only occurs in recession areas where two generations can reproduce successively and quickly. When we find an infestation of these gregarious locusts over a year or more, we speak of « plague ». A major scourge exists when two or more regions are affected simultaneously. Locusts then tend to migrate beyond the recession zone. This type of invasion generally takes several years to develop after a series of events during which locusts regularly increase their numbers. This type of outbreak would take approximately 6 months to naturally decrease, which is faster than it takes to develop. This decrease in numbers may be linked to natural deaths and / or migration.

However, the invasion of locusts has continued since the beginning of the year. It is considered by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to be the worst in 70 years. It is a major threat to food security.

The relationship between climate change and the locust infestation is a particular concern to scientists. In recent decades, temperatures have increased as well as the level of precipitation. These conditions appear to favor the appearance of more destructive locusts.

These precipitations are explained by cyclonic activity located at the dipole of the Indian Ocean. There is a pronounced temperature gradient (variations) which is associated this year with the major fires which took place in Australia. If this frequency of cyclones increases, it is possible that events related to locusts also increase.

Regarding the invasion which is still current, it is linked to two cyclones which allowed three generations to develop in the best possible conditions.

A first migration had taken place in August 2019 across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to invade Ethiopia and Somalia. The result was an unusually intense aggregation of locusts in East Africa, resulting in huge clouds of individuals.

.A new cyclone then caused heavy rainfall in this area, further increasing the locusts’ reproduction. A cloud invaded Kenya in December, then spread in January to Djibouti, Eritrea, then Uganda and Tanzania. Following these events, scientists fear that the locust population will increase sharply again in June.

The destruction of agricultural crops caused by these locusts is not without consequences. Indeed, this affects regions that are already experiencing famine. More than 13 million people face « severe food insecurity » according to the UN. Another 20 million will suffer the same fate. Food deprivation affects humans but also fauna and livestock. Prevention methods such as meteorological studies to predict the increase in the locust population are, however, in place. As well as measures to protect crops with the spraying of pesticides which has the negative impact of eradicating both wildlife and « useful » insects for farmers and pollinators. Research is underway to establish a biological control against the invasion of these locusts: the aim would be to introduce species which would compete with the locust and thus reduce its population. At this very moment, these countries are still fighting to face this huge wave of famine, this combined with another invasion that makes access to food even more difficult, that of the Coronavirus, or Covid-19.

References :

1. Claire Cosgrove. Desert locusts are swarming with greater Ferocity. Echoing Sustainability in Mena. 2020.

2. Keith Cressman. Desert Locust. Biological and Environmental Hazards, Risks, and Disasters. 2016.

3. Michel Lecoq. Preventive management of the desert locust and the ongoing invasion.

4. Sayantan Gosh. Desert locust in India: The 2020 invasion and associated risks. EcoEvoRxiv. 2020.

5. Yiftach Golov. Sexual behavior of the desert locust during intra- and inter_ phase interactions. PeerJ. 2018. Desert locust ecology and control strategy. 2020.

Comment ( 0 ) :

Subscribe to our newsletter

We post content regularly, stay up to date by subscribing to our newsletter.